Today, we’re taking a deep dive into the farewell dinner that La Plaza hosts each year to honor and celebrate the efforts of that year’s migrant farm workers.

Join me as I find out what it takes to prepare and serve dinner and a party to more than 100 migrant farm workers and their families, to say thanks (and see you next year)!

Subscribe:

Transcript:

(fade in to sound of cheering)

This is Postcards From Palisade. I’m Lisa McNamara. Today, we’re taking a deep dive into the farewell dinner that La Plaza hosts each year to honor and celebrate the efforts of that year’s migrant farm workers.

Join me as I find out what it takes to prepare and serve dinner and a party to more than 100 migrant farm workers and their families, to say thanks (and see you next year).

Dinner guest: Gracias! Hasta luego!

Iriana: Hasta luego! My name is Iriana Medina and I am the executive director at La Plaza. The purpose of the farewell dinner, it’s to honor and say thank you to the workers for the hard work that they’ve done throughout the season. We just have a, not just, but we have the chef volunteer who puts her crew of volunteers for the kitchen together and then we get, we do our part on getting a crew of volunteers too to put this together. You know, the party part, like, you know, setting all the chafing dishes, all the food, bringing it out here, tables, chairs, all the logistics that a party has, pretty much. Music, of course, because music is very important.

We also collect donations throughout the year, things that could be useful for them and that they could bring home with them because they, throughout the season, they collect and buy stuff to bring over to their families. And so this is a little bit of something to bring home with them for the families.

They wait for this, and this year we moved it to August because usually we have the dinners on the second week of the month, but by the second week of September, many of them are gone. So we noticed last year that a lot of people missed it. So we wanted to, we were mindful about this. And so this year we’re having another dinner in September, but the farewell, we decided to do it in August so a lot more people could come and enjoy this event that’s made for them.

It’s very festive because they know that there are prizes, they know that there’s not going to be services pushed on them. Not that they get, that we push services on them, it is that, they need services while they are here. So in these dinners, the main purpose during the season is that they can connect with other services that provide, that have programs that are different than ours so that they know they’re available and that they can connect with them directly and be beneficiaries of these services, that those other agencies in the valley have. Tonight, it’s merely fun. And dinner, food, music, prizes. And a big thank you.

(cheering fades out)

LM: The day before, Tuesday, Lynn Foster (aka Chef Lynn), that’s how she’s in my phone, Robin Gale, and I sat down in the dining room at the La Plaza building. La Plaza hosts dinners each month, called resource nights. Chef Lynn plans the menu for the monthly dinners and for the farewell dinner, sources the ingredients, puts together the work plan, schedules volunteers, and cooks much of the meal.

Lynn spends all day Monday shopping and delivering ingredients to La Plaza. Tuesday is the hard prep day in the La Plaza kitchen. Tuesday morning, Chef Lynn reviewed the farewell dinner menu and work plan with Robin and me.

Lynn: Good morning.

Lisa: Good morning. Okay, so just be yourself.

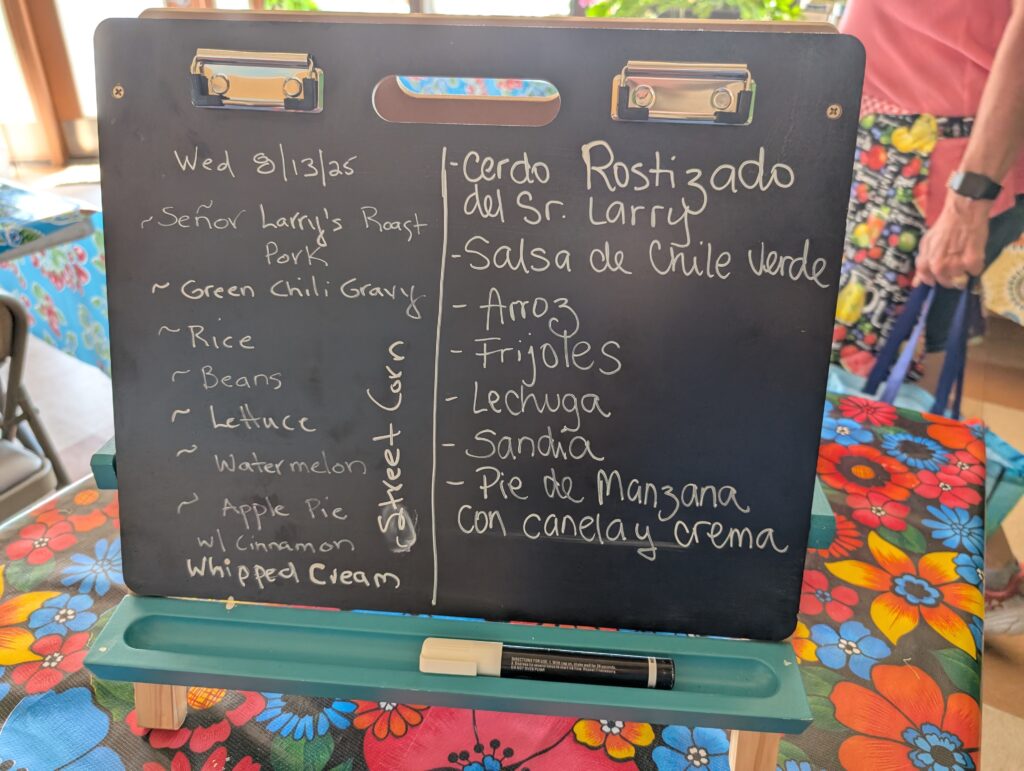

Lynn: I am. So we’re gonna do. Here’s the menu. Roast pork that Larry’s cooking that’s gonna come at four tomorrow, 3 to 4 o’clock. And we’re gonna shred it up with green chili sauce that I’m gonna try and dream up and make good. And rice, beans, shredded lettuce with radishes and pickled carrots. Watermelon, apple pie with cinnamon whipped cream.

Lisa: Okay.

All together: And the corn. And jalapenos. Oh, and of course, pickled jalapenos.

Lynn: And don’t forget, we’re also shucking 100 ears of corn and we’re gonna make that into street corn somehow.

Lisa: Sounds great.

Lynn: I know. Should be. And we’re expecting 100 people.

Robin: And it’s 100 degrees.

Lynn: And it’s 100 degrees and there you go.

Lisa: All right, so what are we doing today, then?

Lynn: Okay, so the corn is in there. I don’t know where you want to do it. Depending on what you’re more comfortable with. You can sit down and do it. You’re gonna make a big mess so I wouldn’t even worry about it. I’d just sweep it up when you’re done. Gail got to do this last time.

Lisa: We may want to sit.

Robin: We may want to sit. Yeah, I’m thinking like a corn shucking party.

Lynn: Yeah.

Robin: So many times we really have to stand. But I think that’s something we can just do sitting.

Lynn: And I’m gonna sort of run around to begin with and just get anchored because I want to start beans. I meant to be making the green chili, but then I forgot the green chilies. That’s okay. I can start it today. So I want to put my rice…

Robin: I have green chilies.

Lynn: No, I have them.

Robin: Oh, just not with you.

Lynn: Right.

Robin: They’re at home.

Lynn: So they’re all in the refrigerator. No, I have a whole big bag of big jims that I got at the market on Sunday and…

Robin: Yeah, that’s exactly what I got.

Lynn: Yeah, love them. I love that guy. All right.

Robin: Okay.

Lynn: So, yeah, here we go.

Lisa: Alright, let’s do it. Corn.

Robin: My hand will be very tired. And that’s using this. Using my brain.

Lynn: Mine would be crippled. Okay, ready?

(corn chopping and shucking sounds)

Robin: Look at that.

Lisa: That’s pretty great. I oh, I didn’t do that one very well. Do we want any knob left on this side, or do you think we want it totally off?

Robin: No, I think we take the knob off.

Lisa: Okay.

Robin: This part of the knife. The heel.

(corn chopping and shucking sounds)

Lisa: I’m going to have to refine my technique a little bit.

LM: OK, imagine these noises continuing for an hour, which is about how long it took the two of us to get through the corn. After Chef Lynn, Robin, and I worked through Tuesday morning and got a good chunk of prep done, we took a break and I asked Lynn to explain how she plans the menus each month, where she sources the food, and why it’s so important to her to make a delicious meal with high-quality ingredients.

Lynn: I think about it a lot. Like, depending on what we have, how many people are going to have, you know, at the beginning of the summer, I think we only did 38 and now we’re doing 100. And this will be the third time we’ve done a hundred people. So depending on what we have, I write a list, decide what I’m going to do, see who my volunteers are. So for instance, this time we just shucked a hundred ears of corn because we’re going to attempt to make street corn on the fly on a griddle. And I just kind of work it from there. And depending. So we have a stove with eight burners, but it doesn’t have ovens. So we’re extra challenged. So I’ve got to have something I can boil or cook on actual flame burners. Or we have a butane griddle outside that we use out there. So those are what we have to work with. Or sometimes we talk a lovely neighbor into roasting all the pork for us, which will arrive tomorrow, which is great. So it just kind of works itself.

This time I’m doing apple pies, which I happened to source from Sam’s Club. But they’re delicious. But to make them a little fun, I’m gonna make fresh cinnamon whipped cream, which I think will go over big. And our members are just, they’re so appreciative. And this time, we do watermelon almost every time, because we know they’re dehydrated. They’ve been working so hard all day. Make sure there’s lettuce and there has to be pickled jalapenos. Our members, our farm workers, love whole pickled jalapenos, which can only be found from one location. And oftentimes they’re out. So. And I get the number 10, which is a restaurant size can for them. And they eat them all.

The lower the stature of the person, the higher the quality I’m going for. I start on Monday, I come to La Plaza, I pick up some gift cards. I go to first I go to Sam’s Club. Yesterday that’s where I got the meat and the pies and the limes. Then I go to Shamrock and get the pickled jalapenos. And then I go to Walmart, who has what I think is the best selection of and the most reasonably priced Mexican ingredients, to get my jalapeno, my roma tomatoes, my white onions. And this time we have a special lady that comes down from Olathe and brings a truckload of corn every day. So I communicated with her and along with the grocery shopping, I picked up a hundred ears from the corn lady in front of the Jiffy Lube.

And, and you know, and then, okay, so Monday I go gather it all up. Had to drop the pork off. Come here. They help me unload, get it in the refrigerators. Then at 8:00 last night, I knew where there were really good watermelons. So I went and bought three really good watermelons. Because it’s so worth it. Like it’s just so. For me, it’s so worth it. Like, if I’ve always said if I’m gonna work this hard, it should be really good, otherwise why would I work so hard?

Okay, so then Tuesday, this is our Tuesday. And now we prep. And I get really willing people to come in and do the really heavy prepping. While I’m running around putting the rest of it together, I’m making the first vat of green chili sauce I’ve ever made. And I know what I want it to taste like. We’ll see how it turns out. I can make anything pretty good to eat, so I can just sort of throw it out there.

So then that’s today and we’ll finish this up. I’ll go home and rest up and then we come back tomorrow and we will finish everything up. Get it ready. We’re having, the guys have been coming in at five, but now they need to stay in the fields longer. So I’m happy to know that we’re going to start not till 6:30 so we can get more guys.

And as an aside thing, one of my favorite things is seeing these guys that have worked so hard that maybe, you know, you sort of have the. They all. You think they all know each other, but maybe they don’t. They’re from different parts of Mexico. And so to get here, to come here and socialize and hang out with each other and then eat a really good home cooked meal that’s so satisfying and they’re so appreciative.

Geri just rolled in and Geri makes a lot of stuff happen. For me as a volunteer opportunity, the fact that I can be here and it’s not formal is why I can be here. Because I’m not formal. I’m not a committee. And again, they just work with me, whether it’s how cranky I get or…

LM: Geri had brought over a huge chile relleno burrito from “the burrito lady” and as Lynn and I chatted, Geri carved us off generous slices. Throughout the day, La Plaza staff pop in and out of the kitchen, offering samples of whatever snack they’re having, taste-testing our dishes, and giving advice. After we enjoyed a delicious little burrito snack, I asked Lynn why she volunteers to plan and create these meals. Geri was quick to pipe in.

Geri: Because she’s wonderful!

Lynn: This is my third full year, and I tell people, this takes a lot out of me. I’m almost 72 years old, but I still love to do this. And not everybody can do this. First of all, I’m a generous person by nature. And then I. You know, I have famous friends. They write cookbooks. They are on. I have one friend that’s all over Food Network. God bless her, and yay. But all I ever wanted to do was literally feed people. I’m very clear on that. That I just want to feed people. So anytime I can think up a time to feed people, I do. Then, this is an enormous effort. It’s an enormous undertaking. But to know that I can still pull it off and that those hundred people all get something, there’s a portion for everybody. It’s. It’s like food that shocks them. It’s so good. I think that it’s a little bit, like, macho ego or something, or just there’s a small part of that, just like. Well, because I’m. And my husband says to me, when I first met. When I was first with my husband, I went off to feed 120 kids in Baltimore, and I made meatloaf with them in a small kitchen. And he was like, who’s paying for this? And he quickly learned never to ask such a silly question again, because it’ll get paid for somehow. And if part of it is mine, that doesn’t even occur to me, because there’s a mission here. We’re going to make this meal. We’re going to have a great time. And, you know, and I’m tired for three days after I do this.

Robin said, yeah, I needed Advil after a couple hours with Lynn. And it’s true, especially the schlepping. And of course, I have to get you guys to do that now. I did a lot more of that for so. I worked pedal to the metal for 20 years straight. Just worked myself and loved it because I love cooking and I love food, and I love anytime I can learn a new thing. What was I was telling you today, I learned the other day in Sam’s Club, a Mexican woman said to me, oh, those pinto beans look so fresh. Where’d you get them? I said, well, you know, they’re right there on the shelf. I didn’t realize pinto beans. I know that beans can get old, but I didn’t realize I could look at them and know from the color. So I learned a new thing that day.

LM: The La Plaza kitchen is not huge. It’s a commercial kitchen, but it’s tight. And during dinner prep or tamale making, it has to do many things at once.

Lynn: So in the three years I’ve been here, this place has come up a long way. When I first came in here it was Liz and Shad Dirks. I just put out on Facebook, I’m cleaning the migrant kitchen. Do you want to come help me? And they showed up. Well, Liz like dazzled. Oh my God. That woman just, you know, restaurant animals, you know them when you see them. And Shad too. And he and I, we also do the tamales, which I didn’t want to do tamales but I do the tamales and we do. Our record was one Christmas we did 562 tamales. And again that’s a three day process too. But so they came. I know I’ve thrown out, I’m not exaggerating 90 pairs of those stupid plastic tongs you get when you get carry out food that don’t work and they break. And every time I come in and find more I just throw those out too. But at any rate, back in the day they used to feed the migrants every day. So we had like 200 plastic glasses like you’d see in a diner. And so we just have been purging and purging and trying to keep it to what we do use and also bringing in equipment that we do need.

For two of those years we were sharing a refrigerator with our friend Oscar who owns El Rey Mexican Food. And we all worked out of a single door professional refrigerator. And it was, it was a challenge. And now we have a double door refrigerator all to ourselves. That’s amazing.

Lisa: And Oscar has his own restaurant!

Lynn: But we have this used stove that just doesn’t do much. It only, it has eight burners. It served its time. It belonged to one of the restaurants in downtown Grand Junction. For a long time. They donated it to us. My philosophy is stop taking donated equipment in a setting like this, because it costs you money and it doesn’t work right. But at any rate, so we’re now working on getting a new stove which we’ve got some donations and I think we’re close and I may go, we like to go to the farm market and introduce our, I may put on my chef’s coat and go take a little tin cup and see if I can raise the money. Because we really do. When we have a stove, we’ve got a fully, that kitchen can do anything. Like my challenge, but I keep trying anyway, is to make decent rice. Cause it can’t get hot enough soon enough. We’ve come close. It’s been edible, but I haven’t like, nailed it. And, I mean, it’s rice for goodness sake.

LM: So that’s what goes into the menu planning and ingredient sourcing, as well as the creativity and flexibility that is needed to make these meals come together.

Let me just recap the menu for the farewell dinner. This is all made by hand, from scratch. We’re having:

-

Roasted pork smoked offsite by Robin’s husband, Larry (as an aside, the previous month, the pork had been donated and cooked to perfection by Matt Payne of Chicken Grit Farms).

-

Continuing, warm green chili to serve with the pork.

-

Spanish rice with tomatoes, onions, seasoning (where I learned there is such a thing as tomato bouillon!), carrots, and peas.

-

Pinto beans, seasoned with fresh Mexican oregano and cooked up from dry beans.

-

Shredded iceberg lettuce with chopped scallions, grated radishes, and picked carrots. More on the shredded lettuce soon…

-

Wedged limes.

-

Whole picked jalapenos (which, yeah, those come from a can).

-

Sliced black diamond watermelon, because it’s tastier than “regular” watermelon.

-

Street corn, made from the best sweet corn from Olathe’s corn lady, parboiled, then grilled by Tyler Hopkinson (outside in 100 degree heat), then topped with a particular brand of lime mayo, chili powder, and cotija cheese.

-

For dessert, apple pies (from Sam’s Club due to the lack of oven), topped with homemade cinnamon whipped cream.

-

Oh, and I forgot, the tortillas that needed to be steamed at the last secondto bring the whole meal together.

Phew, that’s a lot, right?

So day one, Tuesday, was hard prep day – taking care of the things that take time and that can be done in advance. Shucking the corn, grating the radishes, starting the beans. And always dishes, constant loads of dishes, run through the small, very warm and very noisy commercial dishwasher.

On day two, Wednesday, Chef Lynn, Robin and I were back at it. Day two is execution day. Earlier in the day, the soft things can be done, things like shredding the iceberg lettuce.

Now, if it was me making this meal, I would buy large bags of pre-shredded iceberg lettuce and call it a day. I buy pre-shredded lettuce for myself at home and it’s good enough, right?

It is not good enough for Chef Lynn. Let me tell you about Chef Lynn’s method for producing the best shredded iceberg lettuce:

-

First, you start with whole heads of iceberg lettuce.

-

Cutthe heads into quarters, then run each quarter through a mandolin slicer.

-

Place the shredded pieces into a big bowl of ice water to soak as you work.

-

There’s always pieces that won’t go through the mandolin, so I slice them by hand because I can’t bear to throw them away.

-

Once the bowl fills up with shredded lettuce, rinse and drain it in the food prep sink.

-

Then spin the shredded lettuce in a salad spinner in small batches (no more than 3 handfuls at a time) to fully drain off the water.

-

Line a large tub with paper towels. Put the drained lettuce in the tub up to one inch deep.

-

Add another layer of paper towels and another layer of shredded lettuce, over and over again, until the tub is full.

-

Place the tub in the fridge to fully cool.

-

Closer to serving time, take the shredded lettuce out of the tub, remove the layers of paper towels, and move it into serving platters, topping it prettily with rows of sliced green onions, shredded radishes, and pickled carrots. Fill three serving dishes with this pretty mixture, then back into the fridge they go.

Robin and I did this with 10 or 12 heads of iceberg, taking turns between slicing and draining as we each filled the bowls. It probably took an hour to get through it all.

I think this process perfectly captures Chef Lynn’s care and dedication to absolute perfection. Who else would put this much effort into the shredded lettuce?

After Robin and I had finished our shift on Wednesday, we took a breather with Chef Lynn on the couch in the break room, before the next shift came in to do the final prep and get everything over to the gym, where dinner was being served by shift three.

Monthly resource night dinners are usually served at La Plaza’s offices, but the farewell dinner was being served at the Town of Palisade gymnasium, so as to accommodate the large number of people expected in one single, air conditioned room. That posed a few extra logistical challenges, but we had had time to start staging for the next team who would take everything over to the gym.

I asked Lynn how she felt that morning coming in. The sound quality is a little rough here, because we were all a bit exhausted.

Lynn: I felt great coming in this morning. You know, we’re all organized and we’re good and I think we have a spectacular dinner. That’s what I think.

Robin: And it, to me it’s like a summer. It’s a great summer dinner.

Lynn: It’s like a feast.

Robin: It’s like a feast. All the beautiful corn, the watermelon that everything is going to be so fresh. They are going to love it.

Lynn: And my cinnamon whipped cream is going to turn out. It’s gonna be beautiful. This is the execution day. Because you, make it all. It all comes together. So we have three more volunteers coming in. One who is going to be out in the 100 degree heat charring off the corn for our street corn a hundred ears. And then we have two other people that will be keeping this going and sending everything across the street. And we’ll have volunteers who will be running it across the street and carts.

Lisa: And, your husband cooked all the pork yesterday, right.

Robin: Larry was the pork master yesterday.

Lisa: He’s going to bring it all over later.

Robin: When he saw how many pork butts were in Lynn’s car.

Lynn: They were on sale. So I got a couple extra and I pull up and he goes, you only told me 5.

Robin: Why do you have 10? And got them all shredded for us last night. He shredded it and he degreased all the stock, leftover stock.

Lynn: The leftover liquid from it and he soaked it in everything in apple juice. So it. And then I made my first ever green chili sauce, and I put sausage in there and used the stuff that he had leftover from the pork. It’s a team effort. And I think this says something about our town, because if you ask people to volunteer here, they’ll shock you. They’ll just. They’ll show up. And it might not be 10 people, but you didn’t need 10 people. You only needed two. And two people show up.

Robin: Absolutely.

Lisa: Robin, why do you you help?

Robin: Why do I help? It is such a small thing that we can do for the appreciation that we get every time. Every time you eat a peach here, I mean, it is. We are in an amazing place, and I couldn’t be out in the heat like they are all day. I could not do it. And it’s just a one little, little thing that we can do to show how appreciative we are of the work that they do for us.

Lynn: And I think they know it. I got asked the question earlier today. I tend to leave because I’m exhausted after three days, and I just. I’m too spent to be here. And I was asked, don’t you want to see the people appreciate it? And I very much do. And as a chef, when I get a dining room full of people that were chattering away, but they get a plate of food and it goes silent, you just know you hit your mark because, yeah, they’re conversing, but then suddenly they got to get busy eating what you just prepared for them. And they do. And sometimes, a lot of times I do walk out as they’re just as they’re coming and they say here’s the chef. And they cheer me and that’s all. And also see if I know it’s good. I don’t. I don’t need to see it because I already know. And I did it on. I went to that trouble on purpose and meant every single thing.

Robin: And there’s no leftovers. That’s how you know.

Lynn: Oh yeah.

Robin: There will not be leftovers tonight.

Lynn: Just thank you for doing this though, because this was. This is fun. And I’m looking forward to seeing how you splice up make me sound sensible.

Lisa: I really appreciate how you organize everything here…

LM: I was sitting too far from the mic during this recording, so my sound quality further deteriorated here, but I went on to tell Lynn “I really appreciate how you organize everything here. It’s like multi dimensional chess in your head. You kind of have everything thought through and every detail planned out. And I appreciate that you make me feel useful too. Because I think a lot of times when I volunteer places, if they make you feel like they don’t really need you, why would I go back?”

Lynn: Right. Oh, well, that’s a nice compliment. I appreciate you appreciating me. The sense I have is that people like the direction. It’s like, not everybody could do this. But if you do righteous, perfect, like, she was just saying, all this perfect food, you can feel so good about it because you know that I didn’t give them any old thing. I gave them. I showed them how much I care about what they’re eating.

LM: Let me tell you a few things about Chef Lynn. When you walk into a kitchen where she’s in command, whatever kitchen it is, wherever it is, it’s HER kitchen (like any good chef). I first met Lynn shortly after we moved to Palisade. Paul and I hosted a post-Olde Fashioned Christmas parade Bike Palisade group party in the shell of our then-new home. We’d only had possession of the place for a few days, and I thought, what better way to inaugurate it than to host a party? I had to clean it anyway. Might as well make it nice and dirty first!

I didn’t know Lynn yet, but I was told that she’d be dropping off some chili for the party. We didn’t even live at the house at that time, so I rolled over to let her in before the parade. She was already there. She had bags and bags of things. The crock pot with chili – asking me which outlet was a good outlet to plug it in. I had no idea – I didn’t even know which outlets worked yet! And then there were the garnishes: cheese and I think probably onions and some kind of chips and probably some hot sauce. I’m sure there was more. And also bowls, spoons, and napkins. Things we didn’t have there yet. (Also, shout out to Gail Matthiessen for bringing over a few rolls of TP, which we also didn’t have at the house yet!). That warm chili was the perfect thing after a cold December night bike ride, and a great base for the keg of Palisade Brew that Mark Williams brought over.

But back to this kitchen, the La Plaza kitchen. When you’re in the kitchen, Chef Lynn tells you stories and if you’re wise, you realize those stories are lessons. What you take away from it is: don’t ask her where something is if you haven’t put in a good faith effort to find it first. Don’t ask her how to do something if it should be obvious. Remember the steps that she told you. When she corrects you, pay attention. If you drain that first batch of shredded lettuce and pile it up, then go back with the second batch to find that your piles have been scattered about loosely, so as to better dry – understand that and don’t pile it up again. Scatter it loosely.

Lynn’s always observing what you’re doing, how you’re doing it, and how you’re interacting with others. She decides who she wants doing what, when. So much so that it’s an honor to get a text from Chef Lynn asking if you’re available to help with a specific task. You’re not volunteering so much as being selected to volunteer. It’s an honor and if you’re wise, you accept it.

LM: After day two’s prep shift, I went home to eat dinner and ice my foot, then I went over to the gym to see how the night was going. When I arrived, the gym was full of cheering – La Plaza team members Iriana and Anahi were in the front of the room, giving away prizes. A big boom box played in the background between announcements in Spanish of the prize-winning numbers. Empty plates sat stacked on the tables.

A group of volunteers stood behind the almost fully-depleted trays of food, waiting to serve any last-minute arrivers. La Plaza team members Geri and Amanda were at the intake table and Augusto moved through the room, chatting with people and shaking hands.

The younger kids in attendance helped pull prize-winning numbers from a shoebox, in between running around the gym and generally having an awesome time. One of the littlest kids hugged Geri’s legs and wouldn’t let go. She smilingly brushed him off, but I could tell she didn’t really want to.

As the prize-winning numbers were pulled, big cheers went up from the tables. Everyone was smiling and laughing, excited about winning prizes either they or a family member could use. And the prizes ran the gamut. Everything from the last pie that hadn’t been needed that night to shoes, toiletries, curling irons, kitchen appliances, lawn chairs, blankets, jackets, and a spectacular pair of crystal-studded, blue cowboy boots that Anahi showed off throughout the drawing, building up excitement. It was a happy, festive atmosphere.

Towards the end of the evening, I talked with Amanda about the dinner and the prizes.

Amanda: My name is Amanda Perez. I am the community navigator here at La Plaza.

The farewell dinner is just, it’s a great opportunity for us to get together as a community and celebrate our local farm workers. This is a fun event that we get to put on every year, to give a, you know, a nice farewell to these guys, let them know that they’re important and that we love having them here.

So we do a raffle at each one of these farewell dinners. We’ve been collecting items since probably January, I’m sure, at least. Every time we get donations in, we’re like, ooh, that would be good for the raffle. And we just have been collecting a lot over the months. And so we’ve got, we had a pretty good selection of items today. People excited. I mean, they get excited about pretty much any of it, but I know especially, like, especially for those that are going back home here soon, they really love to get athletic shoes. Sometimes we give away like, bikes, pretty much anything. I think they’re having. We had some cowboy boots that they’re a little bit out of style, but they just had the funnest time just seeing those. And so, yeah, I think they had a lot of fun with those too. And I mean, they took them all right away.

We had a count of 120, but that was including our volunteers. But so there’s a little more than that with staff and some other people that came to help out. But, yeah, more than 120 people in the gym tonight.

It’s just a really great opportunity for us to get together one more time before everybody heads back home. Just to let them know that we appreciate them and we love having them around. And they’re an important piece of this community.

LM: So thanks to La Plaza, Chef Lynn, and all the volunteers for putting on the farewell dinner and sending a message of thanks home with this season’s migrant farm workers. As our markets fill up with fresh and delicious produce and every bite of a perfectly ripened peach or plum or melon reminds me of how lucky I am to live here and easily access this food, I can’t forget to join in the thank you to those who help our farmers thrive.

Even though this season is wrapping up, La Plaza’s work doesn’t stop. Soon it will be time to make batches of fundraising tamales, continue planning for future seasons, and continue supporting the immigrants who remain part of our community.

There are so many ways to contribute if you want to help. You can buy tickets to Quemando, a salsa concert at Grande River Vineyards on September 6th, that is one of La Plaza’s biggest fundraising events of the year. You can donate money to La Plaza, either in general or for a specific cause, like a new commercial stove and oven for the kitchen. You can donate cool things for next year’s farewell dinner giveaway when you’re doing your 2026 spring cleaning.

If you want to help but are unsure how, you can always reach out to La Plaza at (970) 902-2491 or info@laplazapalisade.org or visit their website, https://www.laplazapalisade.org/.

Thanks for listening. With love, from Palisade.