What did the Colorado riverfront used to look like in the Grand Valley? What are the One Riverfront Commission and the Grand Valley River Corridor Initiative why do they matter to Palisade residents? When will Palisade finally get that riverfront trail connection?

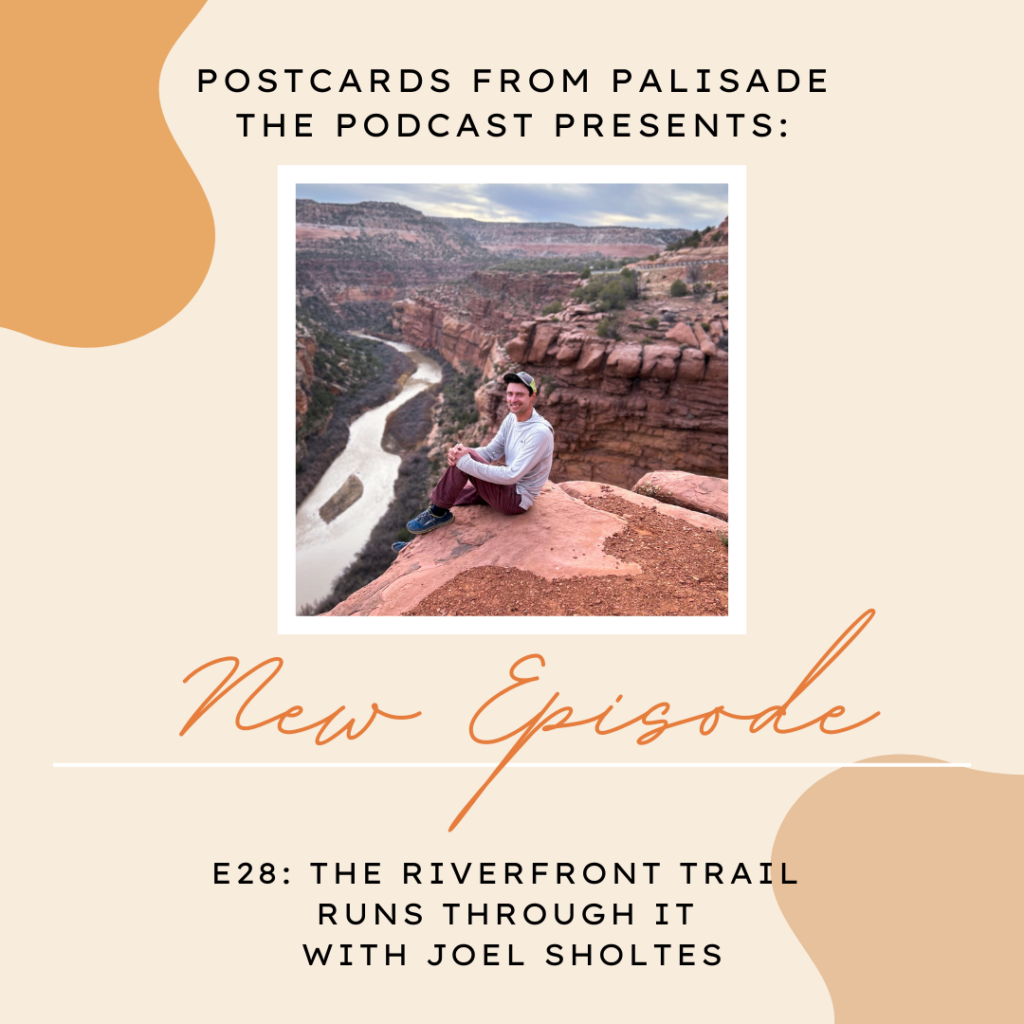

Joel Sholtes joins me to talk about all this and lots more fun river facts. Joel teaches civil engineering, specializing in water resources engineering, at Colorado Mesa University in Grand Junction. Joel also serves on the One Riverfront Commission and the Grand Valley River Corridor Initiative. Join us and think cool river thoughts on this scorching summer day!

More about One Riverfront: LINK

More about Grand Valley River Corridor Initiative: LINK

Music: Riverbend by Geoff Roper.

Photo courtesy of Joel Sholtes.

Subscribe:

Transcript:

Welcome to Postcards From Palisade, where we hear from the people who are shaping our slice of western Colorado. I’m Lisa McNamara.

So I’ve been a little sick! I’ve been waiting for my voice to clear up but now I’m wondering when it ever will?! Then I thought to myself, we all know Ira Glass hosted episodes of This American Life when he was sick as a dog, right? The show must go on. And I hate to keep this great episode from you much longer, so please excuse my nasally intro voice!

Today I am chatting with Joel Sholtes. Joel teaches civil engineering, specializing in water resources engineering, at Colorado Mesa University in Grand Junction. Joel also serves on the One Riverfront Commission and the Grand Valley River Corridor Initiative.

If you haven’t already heard about these groups, One Riverfront is charged with planning, advocating, and implementing programs to redevelop and reclaim the riverfront within Mesa County. The Grand Valley River Corridor Initiative is focused on supporting and maintaining a healthy river corridor.

It’s safe to say that Joel spends a lot of time thinking about water and rivers. He also likes to cycle and he rides his bike over to Palisade every chance he gets. On a Friday afternoon, Joel biked over to chat with me about what the Colorado riverfront used to look like in the Grand Valley, what he’s working on and why it matters to Palisade and Grand Valley residents, when Palisade might finally get that riverfront trail connection, and why you should get involved with the things are important to you.

Hear all about it on today’s Postcard from Palisade.

LM: Good, you good?

JS: Yeah

LM: Well, if you’d like to start just by introducing yourself. Your name,.

JS: Sure. Okay. So my name is Joel Sholtes, and I teach civil engineering at Colorado Mesa University, and I also serve on a couple groups related to the rivers here in the grand valley. One of those is the riverfront commission, and the other is the Grand Valley river corridor initiative.

LM: How is the riverfront commission different from one riverfront? JS: Well, it’s actually the same. It’s mostly the same. Well, there’s been a kind of a long history, and honestly, it’s not that interesting, but it’s one of those administrative histories. The riverfront commission was established by all the municipalities that came on to say, hey, it started in Grand Junction with Watson Islands purchase of, gosh, it was a car dump. I think there were a lot of car dumps on the river, and there’s a real, whatever, locally famous picture of junkyard that you see when you come over the fifth street bridge from Orchard Mesa.

And so that was how a lot of people got to see grand junction for the first time when they came in. So a lot of local leaders, I think, with the Lions club, if I’ve got that right, decided that they wanted to do something about it and, raise some money and worked with the city, to buy that property and really kicked off, probably a decade plus, starting in the late eighties and nineties, restoration effort down on the riverfront. my wife grew up here in the eighties and nineties, and no one, when she was a kid, no one went down to the river. It just wasn’t a thing. Maybe you were a kayaker or a rafter, and you were kind of a little more intense, and you would do that, but the general public wasn’t seeking it out.

So these folks, these leaders, saw an opportunity here. And through that work, also helped establish the James M. Robb state parks, which was named after one of those first leaders that got things going. and the idea was to develop the string of pearls in the grand valley. So we had a lot of industrial uses and farms and, not a lot of development. And really they hoped that we could have these nice green and open spaces that people could connect to. And so that’s slowly been unfolding over the last 30 plus years. Yeah, I’ll stop there.

LM: Okay. Yeah, I’ve seen that picture that you talk about, and it is just amazing that back in the day, the riverfront was thought of as like a dumping ground for old cars. And then there was what, a uranium mine. So that whole effort had to be cleaned up. And when you look at what’s been done in just, you know, 30, 40 years, it’s kind of amazing.

JS: Yeah. And in that area, this is Las Colonias, where the uranium mill was. prior to that it was a beet sugar refinery. And you know, it just kind of shows the different things that we’ve done industrially along rivers. I worked as an environmental scientist on the Hudson river, back in the day and gosh, talk about environmental contamination from our industrial past. so, you know, a little bit of uranium tailings, not terrible. And fortunately it was an EPA, I believe it’s super fund site. I could be wrong on that. But it was in the EPA program and cleaned up and kind of capped and sealed. And now it’s Las Colonias.

LM: Yeah, that’s pretty amazing.

JS: Yeah.

LM: Yeah. So how did you get involved with one riverfront personally?

JS: Well, we moved here for my wife moving back about five and a half years ago. And I’m a river scientist by trade, a river engineer. And you know, I seek out these types of opportunities. So I was like, what’s going on with the river? And so found the website, showed up to a meeting and eventually interviewed to be on the commission. So I’ll just say that it’s a you know, it’s a public volunteer board, kind of like a planning commission or something like that. And we’re always looking for new recruits. So if anyone’s listening to this, look up one riverfront and drop us a line. but that was about, I think, four or five years ago. And have been serving on the commission. Like I said, it’s volunteer. We have representatives from all the municipalities participate, so the county and then the three municipalities. And really it’s a coordinating body. It’s what’s happening on the river, what projects are happening. they have funds through the foundation. So there’s a foundation wing that’s the one riverfront part. It’s a commission and a foundation. So we’re all kind of combined and really try to support efforts. So they will raise money and be kind of matching dollars on grants for extending the trail, writing letters of support for different things and just trying to be a clearinghouse for river and primarily the bike path. That’s our primary focus of projects.

LM: So the bike path, I know one of the things and one of the ways that I got introduced into this or started to learn about it more is, the river path.

JS: They call it the riverfront trail.

LM: Yeah. Like, I know there’s a correct word, the riverfront trail. And moving here. And of course, I love to bike. And, came from Fort Collins, where there’s a ton of incredible trails around town. And you can spend, you know, you can bike hundreds of miles on trails around Fort Collins. So. Got really spoiled by that.

JS: Yeah.

LM: Moved here, love everything else. Looking for some trails, like, well, great, there’s this trail, but it’s over there. And I don’t want to drive to a trail.

JS: It’s a little piecemeal. Yeah.

LM: yeah. So, I started researching a little bit, learning about what was happening already. And then you were leading that ride, the trail connector ride.

JS: about a year ago now.

LM: Yeah, about a year ago. So that’s kind of how I got introduced to the whole thing, that there was an effort that’s been ongoing for years to connect that trail into Palisade and even further up the river

JS: to Clifton and then eventually to las colonias downtown grand junctions.

LM: Right. But then the other way too. Right. Out east.

JS: All the way out. Oh, to east from here. Yeah, yeah. I mean, that’s long, long term. But, there’s one other state park area, island acres, that we’d love to connect to and big, bigger vision. I mean, we’ve got just. You said you talked about hundreds of miles of trails and grand junction. I mean, we’ve got a lot of opportunities, not all them easy, especially, you know, potentially along canals where we have to have willing partners there. but we’ve got this canal that comes the, highline canal. It’s mostly federal project, but that could take you all the way out to Loma, right along the book cliffs. Yeah.

So I don’t know. You know, people talk big, big grandiose ideas, and the only way they happen is through, one little step at a time. And that’s what we’ve been doing with the riverfront trail. It connects out to Loma, where the Kokopelli bike trails are. it goes all the way through grand junction continuously. And then you’ve got that piecemeal stuff. So there’s a segment that, the city, the parks, state parks and, the county have been working on jointly that’s going to connect from Las Colonias to 29 road. so they’ve got all the agreements in place. And actually, it was today or yesterday that they finally signed the deal to purchase the last parcel.

LM: Oh, that’s awesome. I know. It was potentially going to happen. So it actually happened yesterday. That’s great.

JS: I mean, gosh, this is not like, you know, a person going up and putting an offer on a house. This is three governmental entities coming together and, you know, finally negotiating agreements. Really complex, and it’s exciting. So that’ll happen in 26. And then we’ve got this last segment, which comes out to you all here in Palisade. And right now, we’re in this planning project. So we got a, grant from the, local transportation authority, and it’s funding, essentially, an alternative analysis study. So there’s no slam dunk path between Clifton. It’s 33 and a half road to Palisade. It’s the river, which is like, 20 something private parcels. And maybe there’s one of those 20 that’s excited about the trail going through their land.

LM: I can see that, you know, you’re right on the river. like, you’re on the Colorado. How many people get to say that?

JS: Yeah.

LM: Right.

JS: And you have a bike trail going through.

LM: Yeah.

JS: So that’s. That’s probably not going to happen. But we’re looking at alternative routes, and maybe some of them are along the Grand Valley irrigation canal. They’ve got a lot of reasons for why that wouldn’t happen. And as a. As a recreational trail, you’re not going to force your way through.

LM: Right.

JS: You can do, you know, eminent domain if it’s like a sewer line, like Palisade’s doing. Hopefully, it doesn’t come to that for Palisade. But anyway, the point is, we need willing partners, and, this planning project is evaluating all these different alternatives, scoring them based on rideability and feasibility, cost, and then coming up with kind of a recommended route out of that. So we’ll, have a public meeting in July, date to be determined, but kind of later in July that will present that and get kind of public input on these route alternatives.

LM: Awesome.

JS: Yeah.

LM: But do you think that will be held in Palisade or in junction?

JS: That’s a great idea. I think we’re shooting for the Clifton library. It’s a new spot. Yeah.

LM: Oh yeah, perfect. It’s a beautiful spot. Yeah.

JS: So that’ll be the focus for that.

LM: Okay, awesome. And that makes sense. It’s right at the end of the trail about thereabouts. Anyway, that’s a side note. that’s really exciting. So they’ve already completed a lot of the work, it sounds like, and are getting ready to present their recommendation. Is that, that’s the stage that it’s at.

JS: We’re getting there. we’ll have, essentially, here are the alternatives that filtered out, you know, based on all this, just what I say, research and investigation and scoring. get the public feedback, and then kind of take that back and come up with a final recommendation. So we’ll have that final recommendation. Then it’s like, okay, now we gotta, like, design and build it, and it probably will come in phases. Cause it’s a lot. but nevertheless, you know, like I said, one step at a time, and I’m hoping in three years we’ll start to have broken ground on at least one of those segments.

LM: Very exciting.

JS: Yeah.

LM: so how does funding for something like that work? Is it it’s probably from many different sources and?

JS: Yeah. I’m a little frustrated about the funding for trails situation because you think about funding for highways and cities, counties, the state, the federal government. There’s just, it’s baked in. Like, obviously we need roads, we need to repair the roads. I get it. but trails are important. Alternative transportation. They’re really important for the community from a. As you know, just adding value to the community, getting us healthy alternatives, just to get outside and do things and move. So right now, there’s not a lot of dedicated funding to trails. And Fort Collins, pretty sure, they do because they have a lot of trails, and I’m assuming they fund a lot of those internally with their property, sales tax base.

LM: Yeah, there’s a lot of it comes from the sales tax. (Link: https://ourcity.fcgov.com/sustainable-funding-2023)

JS: Yeah. And grand junction does put some of their increased sales tax to trails, but that’s the city. And so here we are. This is a county project. we got basically state money to do the planning project, and if we want to go build a trail, we’re probably going to have to go after some kind of a grant or a combination of grants, and that’s probably great outdoors Colorado or GoCO, they have funded a lot of the trail, and this was one of their initial, back in the nineties, big investments that allowed, us to buy a lot of the parcels where the trail goes through and then also build it. I think I just heard the number today. Someone’s, they’ve invested about 19 million over the last 30 years into the riverfront trail. So, you know, they would be a likely source. But we’re also considering other things like, safe routes to schools. And that’s, I think, a federal program or federal and or state. we’re interested in connecting with, bookcliff middle. Is that what it’s called? Or is it grand mesa?

LM: This, Garfield.

JS: No, Garfield middle. Yeah. and then the high school as well. Palisade high school. So we want to make sure that students can not be on highway six and still get to their schools.

LM: Yeah, that’s huge. that kind of. I was gonna say, why is the trail important? That totally. That answers it. I mean, it’s always hard for me when. When people say, like, why is this something you should be putting money into? Because it seems so obvious to me. It’s hard.

JS: Yeah, I mean, you’re a cyclist. You’re a user of that amenity. When I have heard some, I read it in the paper, too. People are like, why are we spending taxpayer money on, bike stuff? And, you know, bicyclists don’t pay taxes. It’s like, well, they probably have a car. Let’s, you know, just be clear about that. They probably pay gas taxes and other things. but. And then the other thing is. Oh, it’s just like these, whatever elitist cyclists that would use this. I biked out here from grand junction, and I passed teenaged girl on a scooter and then a, longboard, you know, coming out, I passed families, walking their kids in strollers. everyone uses the trail, and if it’s there and it’s easy to get to, you’re not going to be some intense cyclist just to use it. The bar for just getting on the trail and being near the river and getting from point a to point b could be a lot lower. A lot.

LM: Well, that’s exciting. So the process is, develop the plan, get the funding, build it. you think three years?

JS: I mean, that might be. That might be a little. Well, you know, at the end of the day, at the end of this year, we’ll have a plan. And I’m hoping, I try to get this in the scope of work with the consultant, a preliminary cost estimate and a conceptual design. So with that, you’re like, okay, here’s the ballpark of how much this could cost. A plan for implementing it. what do we do from there? Well, I’m hoping the county kind of keeps the ball rolling because they’re kind of tangentially involved. they don’t have a lot of resources, but by them kind of leading the charge with this planning project I’m hoping that that can kind of continue and they’ll continue to be a leader in implementation. Because we are a volunteer board, one riverfront, we all have day jobs and we need kind of, you know, the kind of county level staff to keep things moving for a big project like this. so three years, you know, next year we can start pursuing design and implementation funding. Usually it’s like, design it and that’s expensive. I think the city and the state parks are paying like $400,000 just to design the trail from Las colonias to 29 road. It’s about maybe 3 miles.

LM: And this is more like nine, I think. Eight nine something like that?

JS: Yeah. So the design cost could be really big. I don’t know why we’re paying engineers that much, but I get construction’s expensive, materials, but come on. so, you know, there’ll be like a year of design and then the thing that can be really challenging is just making sure if you have to get new easements through people’s property. And, you know, when we laid out the county, we didn’t plan for this. And so there’s a lot of narrow little roads and telephone poles right next to the road and people’s driveways and fences and vineyards. And you start to play that out over miles and it gets really complicated. So that process of just like getting everything lined up so that we can actually like build the trail. And we want a trail that’s wide, eight to 10ft wide, that’s not just a sharrow on the road. we want it there’s like different levels of ratings of like comfortability or whatever for biking. And we want it to be like that. You know, most comfortable, easiest use, less challenging and threatening, so that everyone feels comfortable using it. And that means like its own thing, its own separated bike path. that might not be possible everywhere, at least at first, but we’re hoping. that’s the standard we want to achieve.

LM: That’s awesome. So, how do you stay patient and persistent through a years long process like this?

JS: Yeah, I think it’s having a great team of people to work with and really good partners to kind of carry things on. Not everyone’s shouldering the burden at once. we do our part, the county’s doing their part, funding gets in the additional capacity to keep things going. So that’s one thing. And then the other is like, you know, I’ll probably be doing this for six years, two terms, and then I’m going to bow out and pass the baton. And as long as we’ve got kind of a robust framework and foundation for how we do things, then people can pick it up and keep it moving.

We had a quarterly meeting this morning with one riverfront where all of our partners and the public kind of got together. And, this gentleman, I believe his name is Brad Taylor, he is now on the foundation. He was a Colorado parks and wildlife, like, district ranger manager, and set the process up, for the last little connection in Grand Junction now, the 29 road connection, getting easements through properties and purchasing the property. CPW owns a lot of the land there. That was in the nineties, and he’s retired. And, that, that process that he set up back in the nineties is, like, finally panning out 30 years later. I don’t know what to say other than, you know, you just kind of keep. Keep picking away and you get new people coming in and. https://www.gjsentinel.com/news/western_colorado/scenic-trail-blazed-to-fruita/article_5d168829-ad2d-5536-b696-cad82b7333da.html

LM: Yeah, kind of think about it with a historical perspective. It’s like geological time.

JS: It feels like geological time. Like, he’s retired now and, you know, on the foundation and not in the day to day stuff, but, you hope that the things you do now ripple and keep propagating into the future.

LM: I love that. Yeah, that’s really cool. And I’m assuming you would be a user of the trail when it’s finally built.

JS: So when we met on the, the bike ride, it was on a lot of roads and we had to cross the highway, and it was lightning and raining.

LM: Yeah. that was the other part.

JS: Can’t do anything about the weather, but we can do stuff about road safety.

LM: That was exciting. You know, it was just. I mean, people still talk about that in our, you know, Monday night rides. It’s like, that was the most epic ride. With the lightning and the rain. Like, blinding rain.

JS: It did feel like a race against time.

LM: Very fun.

JS: You can see a wall of dark clouds chasing after us.

LM: Yeah. No, that was a cool thing to have set up, and I think it brought a ton of publicity to, what you’re doing, what you’re working on, and the need for the trail. So that was cool. What’s your favorite trail to bike? Like are you more of a road cyclist or a mountain biker?

JS: Gosh, I guess I’ll give you two. my favorite little road bike is outside of my house up Little park road. So if I want 40 minutes of just pumping really hard, I get to go up a little park road up to, you know, not quite bangs canyon, but just a little bit before that. So that’s fun. And then, yeah, I also live next to the lunch loops, so get out there. But I’d say my favorite is getting out to Kokopelli and just getting to see the river, from the bike trails out there near Loma.

LM: Yeah. That’s really special. so the other thing that you were talking about then, the river corridor initiative. I don’t know anything about that. So tell me more about that.

JS: Yeah, it’s a little newer, it’s a little more kind of behind the scenes, and it’s a group of, we’ll just say mostly nonprofits. So it’s rivers edge west, American rivers, myself, which I’ll just say Colorado Mesa University. And that’s our core team. And we got together in 2020 and just kind of said, we feel like there’s kind of a missing conversation in the grand valley related to how we manage the land and manage the river corridor. Rivers edge west is obviously, they started out of one riverfront to deal with all the invasive riparian species, tamarisk.

It used to be the Tamarisk coalition. and just managing that because it’s a mess and it’s unsightly and it’s just not good habitat. so they’re coming at it from, how do we manage the vegetation and riparian corridor perspective? You’ve got folks now that are doing, you know, are aware and worried about wildfires on the river. We’ve got these trees and underbrush and how are we managing that?

I’m coming at it from a river science and hazard standpoint. The river moves, it migrates, and it’s always done that. And then when we build roads and bike paths and, you know, there’s a little storage unit, you know, there’s a little storage unit, rental storage unit place that comes right down to the river. It’s like, what do we want? And all these things have been happening over the last several years, I think about what do we want the river to look like as we’re starting to reconnect with it and redevelop it in 20 to 30 years? Like, how can we have the river support all these values that we have?

Obviously, the water, that’s why the grand valley is here, and that’s why it’s thriving. the recreation, the developments, and, kind of economy that’s based around the river and then the environments and the floodplain hazards. I’m a flood hazard guy, so, very aware of that. And I want to make sure that we’re doing all this in a way and we’re coordinating, we, meaning all the local governments and the community, in a way that preserves and supports and enhances those values, because some of the things we might do for one value might conflict with another.

So this has been a conversation. It’s been kind of reaching out and getting stakeholder input about what are the priorities and concerns that we want to address. That was kind of our first couple years, had some workshops and meetings, and then we’ve gotten funding from the state to do these planning projects. So there’s been a, fluvial hazard mapping project. And so it’s kind of a it’s like the floodplain map, but a little bit different. It’s not a regulatory thing. It’s just where has the river been and where will it move, assuming that humans are kind of out of the way. So anything we do in that corridor might eventually get in conflict with the river. So it’s kind of like a heads up planning tool.

we’ve got the endangered fish recovery program, which puts a lot of resources into, supporting these endangered fish. The whole existence of this program, which is supported by the state and water users, it makes it a lot easier to just extract water from the river and put it to use for agriculture and municipal uses. If we didn’t have that program, basically every project would have to go through this really lengthy review process. It’d be really expensive and cumbersome. So it’s really facilitated just, we’ll just say people kind of using the river in that respect.

LM: Interesting. that’s interesting because it feels like from the other things that you’re talking about, there could be a conflict with agricultural uses. So it’s interesting to hear that that’s a big compliment almost.

JS: Yeah, I mean, you’ve got this kind of state law of, we can take water out of the river and put it to beneficial use through water rights. and then you’ve got the federal Endangered Species act, and they can be in kind of a conflict. And so this program, it’s been around for 30 something years, tries to bridge that gap. And, okay, the things that that program does, supports the endangered species act and gives them kind of clearance under that. And then as long as that program exists and it’s kind of meeting its metrics, then we can kind of continue using the water in the way that it’s been used, regulated and diverted. Yeah.

LM: I’m assuming the group of people who set that up was very forward thinking to just bridge the gap between two programs that don’t work well together.

JS: Right, exactly.

LM: That’s interesting.

JS: Yeah. And right now they’re coordinating among like, half a dozen reservoirs in the upper basin releases, because last year was a good year. So they have a little bit of extra to help bump the peak up a little bit. And have that you may have read that article, help the river move, mobilize and create that backwater habitat that supports the fish. so part of my interest as a river scientist is the fact that these fish, they don’t just need water, they need places to go or habitat. And that habitat’s created and maintained as the river migrates.

And so a dynamic river, ultimately supports native fish. And so if we don’t really think about that, and 30 years from now, we’ve riprapped the river from Palisade to Fruita, then we’ve got some problems, and it’s also very expensive. So the river corridor initiative is trying to bring all these groups and all these values together and kind of have some plans and have some big picture discussions about where we want to focus restoration and conservation, where do we want to focus development. And what does that development look like? so we can have a river corridor that’s a little more, ah, in harmony and harmonious across the whole valley, and then supports those values.

So the next, the kind of most imminent step that we’re working on is, getting all the local jurisdictions to sign off on a master plan. And that would be a process we do next year. We gotta get funding for it. But, it would be just bringing everyone to the table and be like, okay, what do we value about the river? What do we wanna do about, what are some guidelines and some recommendations that we all feel comfortable adopting? so that we can have a river that meets aesthetic values and open space values and, economic development values, that sort of thing. So that plan hopefully will happen next year, and that will kind of be like this template of like, what is the river going to look like as we develop it out?

LM: So you are obviously very passionate about this stuff.

JS: Yeah.

LM: And I mean, how do you make time for all of this? Just like, I know you have a day job. I think you have kids, right?

JS: Yeah.

LM: and two boards. And how do you make time for everything?

JS: Yeah, I mean, I’m not gonna lie, I definitely have gotten a little stretched over the past couple of years and maybe over involved and actually, stepped back in my teaching. So I’m doing 60% now in my teaching and service at the university. and filling that in with this kind of work. So it’s paying a little bit. You know, we’re getting a grant. I’m paying some of my time to be involved in this and, trying to make it sustainable in that way. Yeah. One riverfront’s volunteer. It’s a volunteer board, and I put in the time that I can with it.

LM: Sure. Yeah, no, it’s a lot, because I know, I mean. People have grand goals to get involved with a lot of things, but when you actually start getting involved, it’s a lot of work, it’s a lot of time, and I think it’s. It needs people like you who can really commit to it.

JS: Yeah, I mean, I think I’ve gone through that journey getting involved, and, like, we need to do this and this and this and restructure, and. And then I’m like, okay, to actually do all this, it’s a lot. And so what. What is reasonable? And so I think with one riverfront, it was like, oh, gosh, there’s all these things that could be addressed. And then we found that, hey, we’ve got this huge gap in the trail, and right now there’s nothing happening with it. So that was the kind of, like, zooming into that. And thank God we’ve got a consultant doing the work. Right.

with river corridor initiative, it’s like, okay, two years of kind of volunteering and showing up and doing stuff. And then, hey, we’ve got this grant I’m going to build in some time for me to get paid to work and do this. With the river corridor initiative, like I said, we’ve been kind of working behind the scenes with local governments. We don’t have, like, community members involved, but I think as we grow and become a little more formalized, we’re starting to think more about community outreach and engagement.

And outreach is simply just like, hey, we’re doing stuff. Engagement, is like, what do you think? And what do you want to. I’m sure there’s. This is my, like, very loosey goosey definition here. do you want to participate and help with this? And, so. We’re going to be a little bit more public facing with the river corridor initiative, and, it takes. Takes a little work to do that, a little targeted, but that’s something we’re exploring. We’re producing a video that’s going to be kind of like, what is the river? And what is the river corridor initiative?

So that’s something that’s fun. and, I mean, gosh, if anyone’s got a little bit of extra time to go to a meeting once a month and do a little bit of volunteering, there’s so many opportunities out there with, the river. It’s the grand Valley Paddlers association. It’s group rides like you’re putting on. there’s a nascent, I think it’s called grand Valley cycling Alliance. I might be getting that wrong, but they’re. They’re gonna be out there soon. just advocating for this kind of stuff out there in the grand valley. And then there’s the urban trails commission with the city. So there’s just a bazillion opportunities. Obviously, it’s easy to get overextended, but find one and, you know, just show up and you’ll find your way. I’m just gonna put that out there to whomever might be listening to this.

LM: Yeah, call to action! Yeah, I know. I’m sure that the boards and the different organizations always just need people. They need help with people, you know, labor. They need hands. They need money.

JS: Yeah. And it’s so rewarding, because you get to engage with and interact with these people that, I’m friends with some of them, I’m not friends with all them, but I get to see them. And it’s like Jamie Porta, who ran for city council, and who’s just, like, an awesome person, and I get to be in meetings and just, like, catch up, and it’s just an example of a cool person that I wouldn’t normally be hanging out with, but then I get to interact with and engage with. So from just like, a pure social perspective, it’s been cool to, and, meet people like you. Right. So that’s what’s been cool about doing this kind of stuff.

LM: Cool. Yeah, absolutely.

JS: I think I’ve talked my. My head off at this point, so. Yeah

LM: Yeah, this was great, this is you know, really exciting things, and, I mean, I really appreciate the work that you and the whole organization are doing, too. It’s. It’s hard work, and it’s a lot of effort, and it takes time and patience that, you know, I’m glad that you and the team of people working on this has, because it’s a benefit to everybody, and we just get to sit back and enjoy it. So, yeah, just do something.

JS: Sorry, I was just leaning over for some reason and then decided to fall over.

LM: Yeah, this is just an ikea chair here.

JS: I think another thing to point out is, like, even if you’re not, like, involved on a board, it’s just like, you know, call up your city council member, especially the Mesa county folks, tell them, like, why. Why is this important to you? And, or email them. Like, they need to hear from the public, because they don’t necessarily know. They have their own priorities and values, and this is one of them. We’re just kind of one of the, efforts and initiatives out there that they may or may not know a lot about, and maybe not, maybe don’t understand why it might be important for the community.

LM: do you all have anything, like email templates or, you know, suggested scripts or anything like that?

JS: No, but we should

LM: just make it easier for the public.

JS: Yeah, that’s a good point. Yeah. I like that.

LM: Yeah. All right, well, thank you so much for coming in.

JS: Yeah, thanks Lisa.

LM: and taking some time to talk to me

JS: Absolutely.

LM: I really appreciate it.

LM: There’s just something so compelling about Joel’s visual of our roles in life as members of a relay race. Big projects and efforts can feel so overwhelming. Reframing your thinking to carrying a specific task as a team member on the grand stage, doing the best you can, then passing the baton on to the next person. How simply beautiful is that? “people talk big grandiose ideas, but the only way they happen is one little step at a time”

The podcast’s theme music is Riverbend by Geoff Roper.

Thanks for listening. With love, from Palisade.